Chronological span

The forms of consecrated life, institutionalised in orders during the Ancien Régime, can be divided into five groups: the monastic, canonical, mendicant, and monastic-military ones active since the medieval period, to which were added the “families” of regular clerics in the early modern period1Fontes, Serra e Andrade, 2010, p. 40; Franco, 2007, p. 261; Franco; Mourão e Gomes, 2010; Franco, Abreu, 2014; Campos, 2017..

Monastic Orders

The first evidence of monastic life in the territory of modern-day Portugal dates back to the mid-sixth century. The ecclesiastical disorganisation that occurred under Muslim domination and until the Reconquista period enabled the survival of diverse monastic experiences, arising more or less spontaneously around communities linked to the founding families or dual communities with variable proximity to the episcopal hierarchy. With the expansion of the apostolic reform in the eleventh century, many of the earlier monasteries disappeared or were transformed into churches, at the same time as hermitic communities developed in the north of Portugal. The latter would come to adopt Benedictine customs, before their disappearance or absorption, in the course of the twelfth century, by the Cistercian orders and by orders linked to the canonical way of life such as the Canons Regular of Saint Augustine or the Premonstratensians. The ardour that these monastic orders provoked among the faithful during the Reconquest was diminished by the implantation of the mendicant orders and by the social and economic crisis that affected Christendom in the fourteenth century. The rise of movements committed to more rigorous religious experiences in the following century led to the foundation of new monastic orders such as the Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit (Paulists, or Pauline Fathers), Saint Jerome (Hieronymites), whose promotion of the idea of flight from the world and material renunciation attracted many lay people and clerics. The provisions of the Council of Trent on the reorganisation of monastic life imposed a centralised structure on congregations, which was in force until the abolition of religious orders in 18342Paragraph based on Mattoso, 2000a, p. 255-258; Mattoso, 2016; Silva, 2000, p. 233..

Canonical Orders

The canonical forms of life began in the eighth century within communities of clerics attached to diocesan service under the jurisdiction of the bishop, but who identified with the ideals of the early Christian communities in terms of living in common and pastoral ministry. The canonical institutions were reformed in the eleventh century with the adoption of the rule of St Augustine. These entered the kingdom of Portugal in the following century, with the Order of the Canons Regular of St Augustine standing out in terms of its reach and importance, despite the contemporaneous presence of the Orders of the Premonstratensians and the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre. At the end of the Middle Ages, the Portuguese kingdom also welcomed the Canons Regular of Saint Anthony (particularly devoted to welfare) and the Congregation of the Canons of Saint John the Evangelist (Loios). With the exception of the latter, these orders evolved in the early modern period towards more hierarchical forms of congregations, which continued until the abolition of religious orders in Portugal in 18343Paragraph based on Azevedo, 2016; Silva, 2000, p. 233..

Mendicant Orders

The mendicant orders (Order of Friars Minor or Franciscans, Order of Preachers or Dominicans, Order of the Hermits of St Augustine or Augustinians, and Order of Carmel or Carmelites) emerged in the thirteenth century, based on an ideology linked to communal poverty, the apostolate, and missionary activity. In the seventeenth century, the appearance of the Trinitarians and the Mercedarians added to the group of orders linked to this form of life, which by then was already quite diversified due to the different understandings of poverty within the Franciscan order between the Spirituals and Fraticelli. Like the other institutional forms of religious life, the mendicant orders were abolished in Portuguese territory in 18344Paragraph based on Fonseca, 2000, p. 334-337; Azevedo, 2016; Silva, 2000, p. 233..

Monastic-Military Orders

The military orders appeared in the twelfth century following the ecclesiastical reform then underway, the promotion of the crusading movement, and the aid and protection given to pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land. The Muslim presence allowed the early insertion of international orders such as the Knights Templar and the Hospitallers in the Iberian Peninsula, in parallel with peninsular foundations (Orders of Santiago and Avis) with origins in earlier groups of knights organised in confraternities. The military orders in Portugal lasted until their abolition in 1834 and were later transformed into honorary orders5Paragraph based on Fonseca, 2000, p. 334-337; Azevedo, 2016; Silva, 2000, p. 233..

Orders of Regular Clerics

With roots in the regular canons of the medieval period, the orders of regular clerics known as the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), the Clerics Regular of Saint Paul (Barnabites), the Congregation of Clerics Regular (Theatines), the Clerics Regular of Somasca (Somascan Fathers), or Oratorians emerged, throughout the sixteenth century, as a response to the Protestant Reformation and the challenges posed to the missionary activity in overseas geographical spaces6Paragraph based on Barbosa, 2000, p. 355-356.. Like the previously mentioned ones, these orders were also abolished in 18347Paragraph based on Fonseca, 2000, p. 334-337; Azevedo, 2016; Silva, 2000, p. 233..

Normative documents (main)

Monastic orders

- Costumeiro de Pombeiro, dating from the thirteenth century8Ed. Costumeiro, 1997.;

- Privilégios da Congregação de São Bento portuguesa, published in 15899Ed. Privilegia, 1589.;

- Constituições da Ordem de São Bento, published in 159010Ed. Constitvçoens da Ordem de Sam Bento, 1590.;

- Definições da Congregação de Nossa Senhora de Alcobaça, published in 159311Ed. Diffiniçoens, 1593.;

- Constituições dos Eremitas da Serra de Ossa, published in 159412Ed. Livro da Regra, 1594.;

Canonical orders

- Constituições do mosteiro de Santa Cruz de Coimbra, published in 153213Ed. Livro das constituições, 1532.;

- Estatutos e constituições dos Cónegos Azuis (Loios), published in 154014Ed. Statutos e constituyçoes, 1540.;

- Regra de Santo Agostinho e constituições da Congregação dos Cónegos Regulares de Santo Agostinho, published c. 156115Ed. Regra do bem aventurado, 1561.;

- Atas dos capítulos do mosteiro de Santa Cruz, dating from the sixteenth century16Ed. Actas, 1946.;

Mendicant orders

- Atas de capítulos da Ordem do Carmo, dated between 1318 and 190217Ed. Acta capitulorum, 1912-1914.;

- Constituições do mosteiro de Jesus, dating from the fifteenth century18Ed. Constituições Jesus, 1951.;

- Atas de capítulos provinciais da Ordem de São Domingos em Portugal, dated 1567-159119Ed. Rosário, 1977.;

- Privilégios da Ordem da Santíssima Trindade, published in 157220Ed. Instituição & summario, 1572.;

- Constituições da Ordem dos Frades Eremitas, published in 158221Ed. Constitutiones Ordinis, 1582.;

- Constituições dos Frades da Santíssima Trindade, published in 159122Ed. Constitutiones fratrum, 1591.;

- Regra de Santa Clara, published in 159123Ed. Regra da bemauenturada, 1591.;

- Regras e constituições da Ordem de Santa Clara, published in 160924Ed. Regra e constituições, 1609.;

Monastic-military orders

- Definições da Ordem de Calatrava, dated 146825Ed. Dias, 2006, p. 111-142.;

- Estatutos da Ordem de Avis elaborados em Capítulo Geral, drafted in 150326Ed. Estatutos, 1503.;

- Regimento das visitações da Ordem de Santiago, dated 150927Ed. Barbosa, 1998, p. 260-269.;

- Regra e statutus da hordem Davis, published in 151628Ed. Regra e statutus, 1516.;

- Regimento de visitadores [of the Order of Avis] (1516) (incorporated into Regra e statutus da hordem Davis(1516)29Ed. Ferreira, 2004, vol. 2, p. 68-89, doc. B.;

- Definições e Estatutos dos Cavalleiros & Freires da Ordem de N. S. Iesu Christo, com a história da origem & princípio della, published in 162830Ed. Definições, 1628.;

- Regra da cavalaria e Ordem Militar de S. Bento de Avis, written by Dom Carlos de Noronha in 163131Ed. Noronha, 1631.;

- Regimento dos visitadores [da Ordem de Avis], dated 163132Integrated in Noronha, 1631, ff. 133-153v and summarised in Ferreira, 2004, vol. 1, p. 68-79.;

- Definiçoens e Estatutos dos Cavalleiros e Freires da Ordem de Nosso Senhor Iesu Christo com a Historia da Origem & principio dela, published in 167133Ed. Definições, 1671.;

Orders of regular clerics

- Formula Instituti, drawn up by St Ignatius of Loyola in 1539 and approved by Popes Paul III in 1540 and Julius III in 155034Ed. in Portuguese translation at Constituições da Companhia, 2004, p. 29-36.;

- Constituições da Companhia de Jesus, drawn up by St Ignatius of Loyola and published in 155835Ed. in Portuguese translation at Constituições da Companhia, 2004, p. 45-223.;

Competences

General

The regular clergy, bound to a monastic rule, had as their principal mission the service of God through a life of contemplation and introspection, a stable life within the confines of a monastery and separated from the world45Chorão, 2000, p. 274..

The function of the canons regular and the mendicant friars was to carry out the apostolate in urban environments through living in common and individual poverty, without the ascetic preoccupations of monastic life46Azevedo, 2016, p. 173..

The friars of the military orders had as their primary mission warfare against the enemies of the followers of Christ and the promotion of the Catholic faith47Fonseca, 2000, p. 335..

The clerics regular aimed to achieve a greater perfection of the religious life by combining the clerical vocation of preaching, the apostolate, Christian education, sacramental administration, and direction of consciences with the priestly condition of taking solemn vows and living under a rule approved by the pope48Paragraph based on Barbosa, 2000, p. 355-356..

On entails

The traditional monastic orders (Benedictines, Cistercians) were averse to setting up votive chapels in their churches because of their monastic vocation to live “within” the monastery. The Cistercian rules and constitutions, organised in the twelfth century, envisaged that the order’s churches should be provided with chapels with altars in sufficient numbers for the daily liturgical celebration by the members of the community, since each altar in a Cistercian church could only be used for mass once a day49Serbat, 1910, p. 374-375..

The monastic orders founded from the end of the fourteenth century eventually offset this limitation with the possibility of their churches hosting chantries established by members of the elites linked to the welfare corporations established there and identified with the devotional options promoted within these new orders50Rosa, 2012, p. 375; Gomes, 2009, p. 44-45..

The canonical orders, by making the following of a monastic rule compatible with the urban apostolate, welcomed the establishment of multiple chantries on behalf of the faithful51Rosa, 2012, p. 374, 707-709..

Since they specialised in the latter, the urban elites chose the churches of the mendicant convents and Jesuit colleges as spaces for the setting up of entailed chantries52Rosa, 2012, p. 374, 707-709; Mota, 2017, p. 124..

Although the regulations of the monastic-military orders give only sparse information about the chantries instituted in their churches, the definições of Calatrava (1468) obliged members of the order to set up chantries only in churches where they received the sacraments53Ed. Dias, 2006, p. 120..

Institutional organisation and the roles of its agents with regard to entails

Institutional organisation

Monastic institutions were composed of an abbot for male monasteries and an abbess for female monasteries, who exercised their jurisdiction over a monastery made up of monks/nuns responsible for specific tasks (ovenças) and the remainder of the monastic community. The latter shared the interior of the monastic enclosure with the group of novices and various officials responsible for the day-to-day running of the monastery64Coelho, 1977, p. 63–64..

The canonical institutions were composed of a prior in the case of male monasteries and a prioress in female monasteries, who exercised their jurisdiction over a convent constituted by canons/donas responsible for specific tasks (ovenças) and the remainder of the monastic community. The latter shared the conventual space with the group of novices and various officials responsible for the day-to-day running of the institution65Azevedo, 2016, p. 171..

The mendicant orders were directed by a general (Mestre, Minister, or Prior) who exercised his tutelage over the provincials, who were responsible for the aggregation of convents headed by a superior in the case of the male convents (guardian in the case of the Franciscans or prior for the Dominicans; abbess in the case of the Poor Clares and prioress for the Dominicans) and by a community of male friars or female donas66Araújo, 2016, p. 254.

The military orders were characterised by a hierarchy centred around a chief, generally called Mestre, assisted by various dignities (comendador-mor, comendadores, prior, sub-prior, and sacristans, among others), which included the group of friar-knights, friar-clerics, and conversos67Fonseca, 2000, p. 335..

Orders of regular clerics were generally formed by a superior general elected by a collegial assembly, who oversaw a congregation divided into provinces headed by a provincial and composed of various types of members68Moulin, 1967, p. 81-82..

The roles of its agents

Religious orders did not have any officials responsible for matters related to entails. There were no specific regulations to deal with issues related to the administration of entailed assets, so the traces of their existence are tenuous in the official regulations, apart from their inclusion in prescriptions within the scope of one of the correctional and regulatory mechanisms existing in the various religious orders designated as the canonical visitation69On the historical evolution of this mechanism and its application to different types of religious orders, see Baccabère, 1965; Oberste, 1996; Gomes, 1998; Cabral, 2016, p. 21-29..

Since the visitator was authorised to verify and correct the way in which the prelates of each house administered their respective spaces and patrimony70Alden, 1996, p. 247; Cabral, 2016, p. 97, 133-134, the treatment of this specific issue can only be found in the visitation statutes created within the military orders:

- The statute (regimento) of the Order of Avis of 1631 obliges the visitator to inquire into the chantries of the order’s convent, to verify the registry of the respective assets, and to inspect the chantries’ books, wills, and founding documents71Noronha, 1631, tit. 6, reg. 1, f. 135v..

- In the case of the Order of Christ, the visitator should ask the comendadores, knights, and friars, during the visitation, if they set up chantries without a license from the order and in a place belonging to the order72Definições, 1628, part 2, tit. 9, p. 200; Definições, 1671, part 3, tit. 9, art. 6, p. 114., which implies that their construction was dependent on the aforementioned authorization.

- In the case of the Orders of Santiago and Avis, the visitator was obliged to inspect the chantries, in order to verify their respective assets and the fulfilment of the respective liturgical obligations (Santiago 1509, Avis 1516, 1631)73Ed. Barbosa, 1998, p. 268; Ferreira, 2004, vol. 2, p. 82; Noronha, 1631, tit. 6, reg. 2, f. 139v..

Relations with other institutions with regard to entails

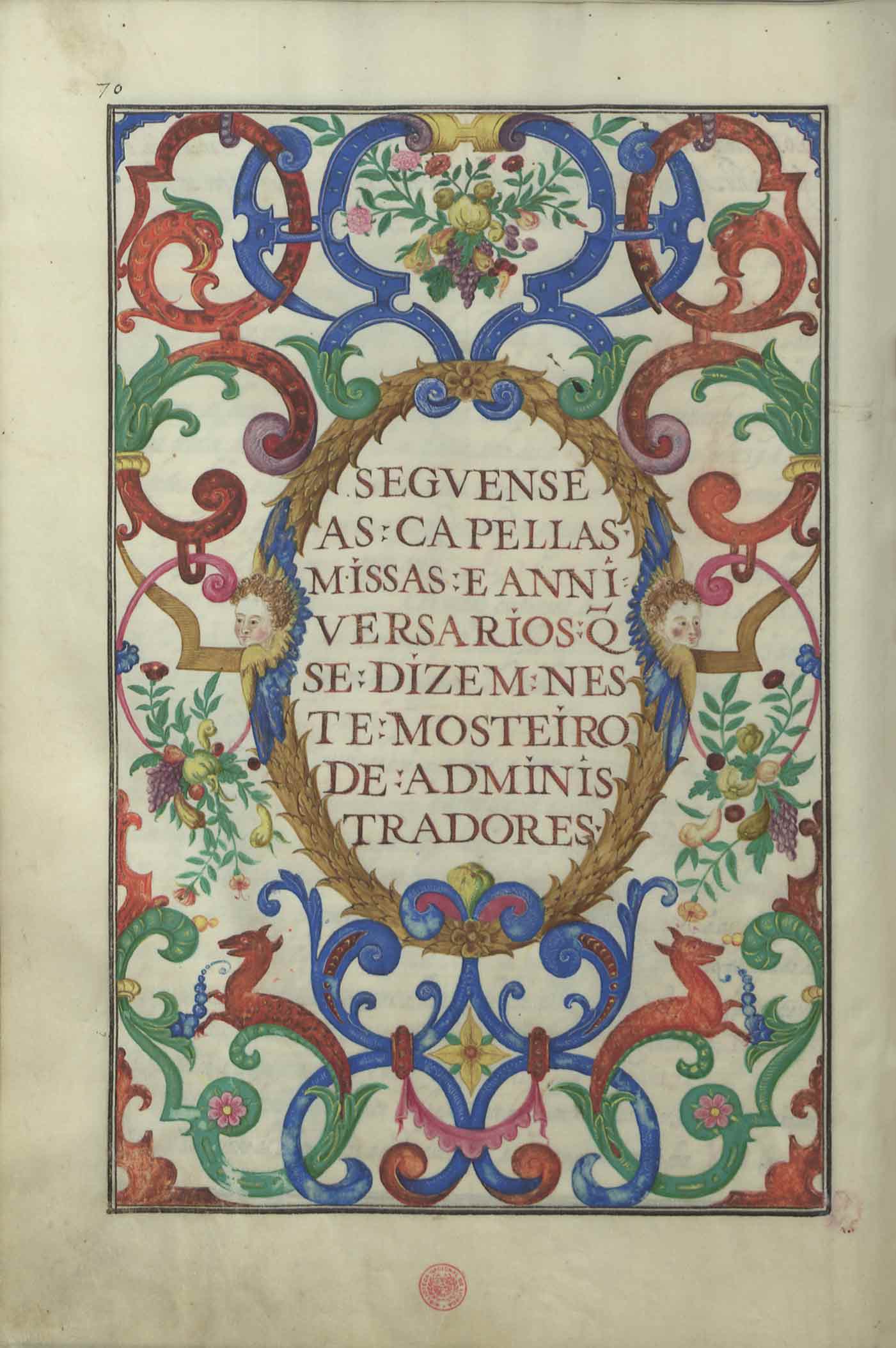

The monastic, canonical, mendicant, and monastic-conventual communities communicated with the chaplains who served and the administrators who managed the chantries set up within their churches, namely in connection with the oversight of the fulfilment of the dispositions established by the founders74Rosa, 2012, p. 584..